What is Radiant Heating?

From Ancient Innovation to Modern Comfort: The Complete Guide to Radiant Heat

Discover the evolution of radiant heating from ancient Roman hypocausts to modern electric systems. Explore how this time-tested technology provides efficient, comfortable warmth that traditional forced-air systems can't match.

How Radiant Heating Works

From ancient Roman hypocausts to today's precision-engineered electric floor heating systems, radiant warmth has provided superior comfort for thousands of years. Radiant heating warms people and objects directly from the floor up, rather than heating air and forcing it through ducts like traditional forced-air systems.

Think of it like the warmth you feel from the sun on a cool day. You feel comfortable even when the air temperature is cool because infrared energy warms your body directly. Radiant floor heating creates the same effect indoors, providing even, consistent comfort from the ground up—with less energy wasted through ducts, drafts, or temperature stratification.

All heat moves through three mechanisms: conduction, convection, and radiation. Radiant floor heating leverages all three to create efficient, comfortable warmth. Here's how each mechanism contributes to your comfort.

Conduction

The "Within-Floor" Transfer

This is the first and last step in heat's journey. The electric heating element (cable or mat) gets hot and transfers heat directly to the surrounding mortar or self-leveling compound.

This warm compound then conducts heat to the underside of your floor covering—tile, stone, or engineered wood. The heat conducts through the floor's thickness to reach the surface.

When you stand on the floor, heat transfers directly from the surface to your feet via conduction—this is what gives that immediate, "cozy" feeling of warmth underfoot.

Radiation

The "To-Objects" Transfer

This is the "radiant" part that makes this heating method unique. Once the floor surface is warm, it acts like a giant, gentle radiator, emitting thermal energy in the form of infrared waves.

These waves travel in straight lines through the air and are absorbed directly by any solid objects in the room: people, furniture, walls, and the ceiling.

This is crucial: Radiation heats objects and people directly, without first heating the air in between. This is why you can feel warm in a room with radiant heating even if the air temperature is slightly lower than with a traditional furnace.

Convection

The "To-Air" Transfer

This mechanism is just as important as radiation for heating the entire space. The air in direct contact with the warm floor surface gets heated (this initial transfer is technically conduction).

As this layer of air warms up, it becomes less dense and begins to rise. Cooler, denser air from higher in the room sinks to take its place, gets warmed by the floor, and also rises.

This creates a slow, gentle, continuous circulation of air—a natural convection loop that gradually raises the overall air temperature in the space, ensuring even warmth throughout the room.

Together, these three mechanisms work in harmony: conduction gets the heat through the floor assembly to the surface, radiation warms you and your furniture directly, and convection ensures the entire room reaches a comfortable temperature. Because radiant heat warms people and objects directly, you'll feel comfortable at lower air temperatures than with forced-air heating—translating to real energy savings and more consistent comfort throughout the room.

Why Install a WarmlyYours Electric Radiant Floor Heating System?

Electric radiant floor heating systems combine the comfort of radiant warmth with the simplicity and flexibility of modern electric systems—perfect for any room in your home.

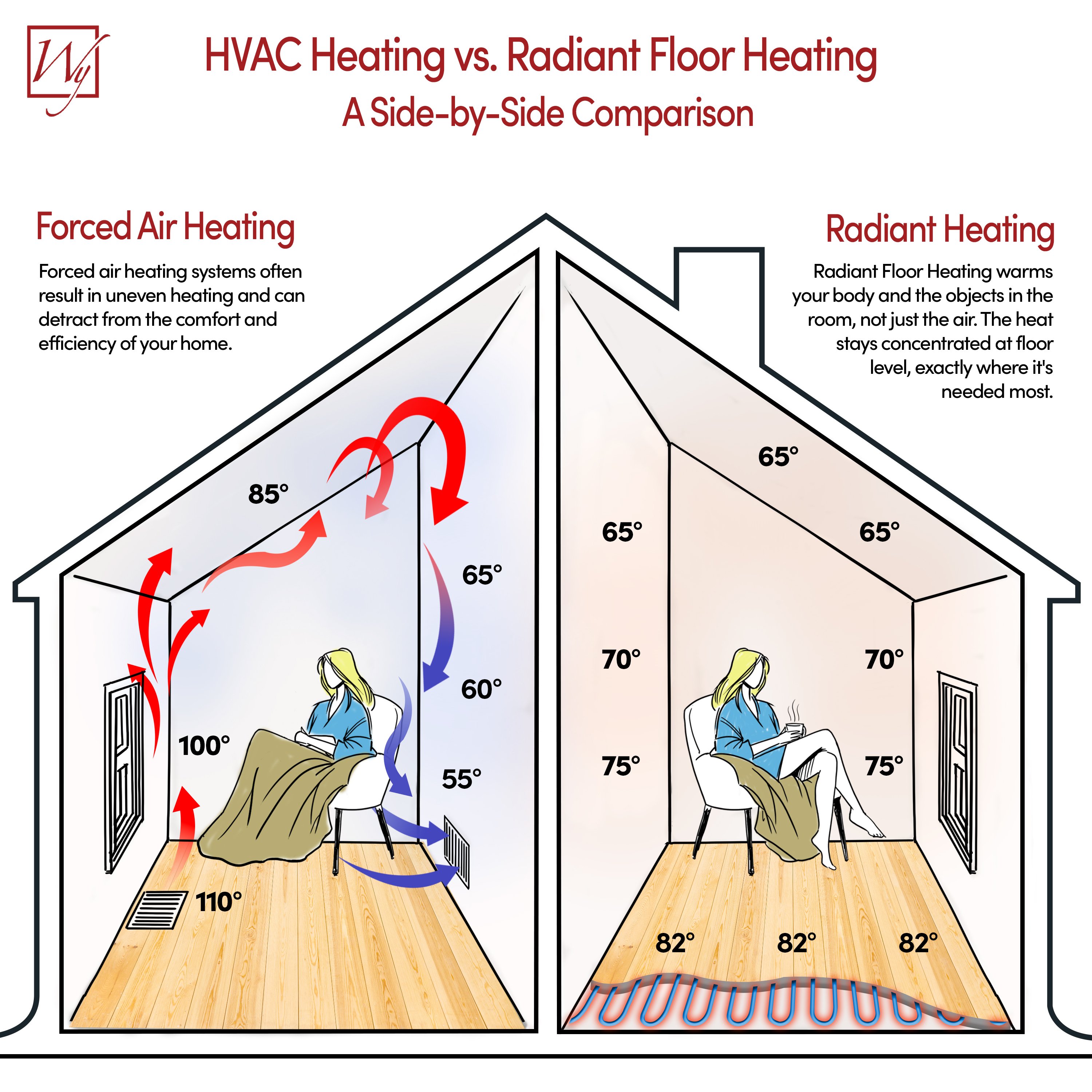

Radiant Heat vs. Forced Air: Why Radiant Wins

Forced-air systems heat air and push it through ducts with loud fans. This leads to drafts, noise, dust circulation, and temperature stratification—warm air rises to the ceiling while your feet stay cold. Energy is wasted heating unused spaces and lost through leaky ductwork.

Radiant floor heating warms people and surfaces directly from the ground up. Heat radiates evenly throughout the room with no drafts, no noise, and no duct losses. You'll feel comfortable at lower thermostat settings, saving energy while improving air quality for allergy-sensitive households.

Read our detailed comparison guide to see which system is best for your home.

Why Homeowners Choose Radiant

- Up to 25% more efficient—no duct losses

- Uniform warmth across entire room

- Whisper-quiet, maintenance-free operation

- Better indoor air quality—no dust circulation

Choosing Your System: Electric vs. Hydronic Radiant Heating

Radiant floor heating comes in two main types: electric and hydronic. Both warm floors directly, but they differ in installation complexity, upfront cost, operating efficiency, and best-use scenarios.

Electric Radiant Floor Heating

Electric systems use thin heating cables or pre-spaced mats installed beneath your flooring. They're powered by your home's electrical system and require minimal maintenance.

Best For:

- Room-by-room zoned heating

- Renovation and retrofit projects

- Fast warm-up for scheduled heating

- Easy DIY installation

Lower upfront cost and simpler installation make electric systems ideal for bathrooms, kitchens, and basements. Smart thermostats minimize operating costs by heating only occupied rooms.

Hydronic Radiant Floor Heating

Hydronic systems circulate heated water (mixed with antifreeze) through flexible tubing embedded in or beneath your floor. They require a boiler, pump, and manifold system.

Best For:

- Whole-home primary heating

- New construction projects

- Large commercial buildings

- Lower operating costs at scale

Higher upfront investment and complex installation make hydronic systems better suited for new builds or whole-home heating. Slower heat-up times can be less ideal for scheduled, zone-based comfort.

From Ancient Times to Your Home: The Evolution of Radiant Heat

Radiant heating isn't a modern invention—it's been warming homes for thousands of years. From ancient Roman bathhouses to today's precision-engineered electric systems, the core principle remains the same: direct warmth that feels natural, comfortable, and efficient. This journey from antiquity to modern innovation demonstrates why radiant heating has stood the test of time.

c. 5,000 BC: Ancient Precursors

Kang and Dikang in China and KoreaArchaeological evidence from China and Korea reveals the earliest known underfloor heating systems. The kang (heated bed-platform) and dikang (heated floor) used fires to channel hot smoke and gases through flues under masonry floors before exiting chimneys, creating radiant warmth from below.

These systems predate Roman technology by thousands of years, proving that the principle of radiant floor heating is one of humanity's oldest heating innovations.

c. 1st Century BC: Korean Ondol

The "Warm Stone" SystemThe Korean ondol ("warm stone") represents a highly refined version of ancient radiant heating. The kitchen firebox (agungi) was set lower than the floor, and a system of underfloor passages drew smoke and heat across the entire room, warming the stone floor which then radiated heat upward. This elegant design would later inspire Frank Lloyd Wright.

The ondol system has been continuously used in Korea for over 2,000 years, making it one of the longest-lasting heating technologies in history.

c. 3rd Century BC–5th Century AD: The Roman Hypocaust

The Original Underfloor HeatingThe Romans developed the hypocaust system to heat their public baths (thermae) and villas. A furnace (praefurnium) generated hot air, which was circulated in a hollow space beneath a raised floor supported by pillars (pilae). The hot air also rose through flues (tubuli) in the walls, heating both floors and walls, which then radiated warmth into the rooms.

Featured in structures like the Baths of Caracalla (212 AD), Pompeii's villas, and Emperor Nero's Domus Aurea. These systems were used throughout the Roman Empire until its fall in the 5th century AD.

5th–15th Century: The Lost Technology

The Decline of Radiant HeatingWith the fall of the Roman Empire in the 5th century, hypocaust systems gradually fell into disuse across Europe. The sophisticated engineering knowledge was largely lost during the Middle Ages. People returned to simpler heating methods—fireplaces, hearths, and later stoves—which couldn't match the even, radiant warmth of the hypocaust.

While some Byzantine structures in the Eastern Roman Empire may have maintained hypocaust systems for a time, the technology essentially disappeared from Western Europe for nearly a millennium.

17th Century (1600s): Early Experiments

Masonry Stoves and Greenhouse HeatingThis century saw adaptations of stoves and flue systems rather than a true revival of the hypocaust. In Northern and Eastern Europe, the Kachelofen (tile stove) provided radiant heat through massive thermal mass. In French greenhouses, builders ran flue pipes from furnaces under floors to protect plants from frost—a technique noted by English diarist John Evelyn (1691), who speculated it might be a surviving technique from classical times.

These innovations kept the principle of radiant heating alive, even if the technology remained primitive compared to ancient systems.

1710–1714: First Hydronic System

Peter the Great's Summer PalaceThe first major application of a hydronic (hot water) heating system is credited to Russia. Peter the Great's Summer Palace in Saint Petersburg featured a heating system, thought to be designed by Swedish engineer Mårten Triewald, that used a central boiler to heat water and distribute it through pipes.

This marked the beginning of using water as a medium to transport heat, the foundation of modern central heating.

Late 1700s: Steam and Warm Air Systems

James Watt and William StruttScottish inventor James Watt, famed for his improvements to the steam engine, built a rudimentary steam-based central heating system for his own house. In 1793, English engineer William Strutt designed a "cockle stove" furnace for his textile mill in Derby, England, that heated air in a central furnace and distributed it via ducts—a forerunner to modern forced-air systems but with radiant properties from the warm ducts.

These innovations demonstrated that steam and warm air could distribute heat throughout buildings, setting the stage for the radiator revolution.

1830s–1840s: High-Pressure Hot Water

Angier March PerkinsAmerican engineer Angier March Perkins (working in the UK) patented a high-pressure hot water heating system using small-bore wrought-iron pipes. This was more efficient and allowed pipes to be routed more easily than the large, low-pressure pipes used previously, making central heating more practical.

Perkins' innovation made hot water systems viable for larger buildings and more complex installations.

1857: The Cast-Iron Radiator Revolution

Joseph Nason's PatentJoseph Nason of New York patented the first cast-iron radiator, marking the return of radiant heating to mainstream use. These radiators operated on the same principle as the hypocaust: metal surfaces heated by steam or hot water would radiate warmth into rooms. While they also heat air via convection, a significant portion of their output is radiant heat.

By 1874, Carr's "Positive Circulating Radiator" improved heat distribution through better steam circulation. Throughout the late 19th century, steam heating became standard in commercial buildings, hospitals, and affluent homes across Europe and North America.

1860s: U.S. Civil War Field Hospitals

Rudimentary Radiant Floor HeatingA rudimentary form of radiant floor heating was reportedly used in some Civil War field hospitals. A fire pit was dug outside a tent, and a trench covered with sheet iron ran through the tent to a chimney, radiating heat upwards to warm the wounded.

This practical application demonstrated that even simple radiant heating could provide comfort in challenging circumstances.

1907: "Panel Warming" Patent

Prof. Arthur H. BarkerBritish engineer Prof. Arthur H. Barker patented a "panel warming" system after calculating that embedding small hot water pipes directly into concrete floors or plaster walls would be an efficient heating method. This marked the true rebirth of radiant floor heating, inspired by ancient Asian systems.

In 1909, Barker's company, R. Crittal & Company, installed his system in the iconic Royal Liver Building in Liverpool—one of the first large-scale modern applications of hydronic radiant floor heating.

1913–1923: Wright Discovers Ondol

Imperial Hotel, TokyoWhile working in Japan on the Imperial Hotel, American architect Frank Lloyd Wright experienced a Korean ondol room and was captivated by the "indescribable warmth" that came from the floor. This firsthand experience would profoundly influence his future architectural designs.

Wright's exposure to ancient Asian radiant heating technology would shape his approach to modern American architecture.

1936: First Usonian Home

Herbert Jacobs HouseWright brought his ondol inspiration to America, incorporating hydronic "gravity heat" into his first "Usonian" house in Wisconsin—the Herbert Jacobs House. He ran wrought-iron pipes in a gravel bed beneath the concrete floor slab, allowing the entire floor to act as a gentle, low-temperature radiator. He believed this was a more natural and comfortable way to heat a space.

This design demonstrated that radiant floor heating could be both functional and aesthetically elegant, eliminating the need for bulky radiators or ductwork.

1940s–1950s: Post-War Boom and Bust

Popularity and Corrosion ProblemsRadiant floor heating became popular in tract housing developments like Levittown, New York. However, these systems often used copper or steel pipes directly embedded in concrete. Problems with corrosion and leakage over the next 20 years gave the technology a bad reputation in North America.

Despite initial popularity, material failures threatened to end the radiant heating revival before better solutions could emerge.

1965: The PEX Revolution

Thomas Engel's InnovationThe technology was saved by the invention of cross-linked polyethylene (PEX) tubing, patented by Thomas Engel. PEX is a flexible, durable, and non-corrosive plastic pipe that made hydronic radiant floor systems reliable, affordable, and easy to install.

This breakthrough led to the widespread resurgence of radiant floor heating in modern construction, solving the corrosion problems that plagued earlier systems.

Early 1990s: Electric Technology Matures

The Breakthrough BeginsElectric radiant heating technology begins to mature with improved cable designs and better integration with floor coverings. Early adopters recognized the potential for affordable, easy-to-install heating that worked with any flooring type—no boilers, pumps, or complex plumbing required.

This breakthrough combined ancient principles with modern technology, making radiant heat accessible without the complexity of previous systems.

1995: Recognizing the Opportunity

A Vision for AccessibilityJulia Billen begins working with electric radiant heating technology, recognizing its transformative potential for homeowners. Her vision: make the comfort of radiant heat accessible to everyone, not just new construction projects.

This personal commitment to accessibility would shape the future of electric radiant heating.

1999: WarmlyYours is Founded

Making Radiant Heating MainstreamJulia founds WarmlyYours Radiant Heating with a mission to make floor heating accessible, affordable, and easy to install. The company introduces DIY-friendly installation guides, responsive customer support, and products designed for real homes.

This marked a shift toward making radiant heating mainstream, not just a luxury for the few.

Early 2000s: Mainstream Adoption

From Niche to MainstreamElectric floor heating gains popularity as homeowners discover its benefits: zoned comfort, energy efficiency, and compatibility with any flooring type. Installation becomes simpler with pre-spaced mats and flexible cable systems.

The technology transitions from niche to mainstream as more homeowners experience the comfort of radiant warmth.

2010s: The Smart Revolution

Connected ComfortWiFi-enabled smart thermostats transform electric radiant heating into an intelligent system. Homeowners gain precise control, energy-saving schedules, and remote access through smartphone apps. Floor sensors provide accurate temperature readings for optimal comfort.

Integration with home automation systems brings radiant heating into the connected home era.

2020s–Today: Universal Comfort

The Pinnacle of InnovationElectric radiant floor heating has become a mainstream comfort upgrade. Today's systems feature ultra-thin heating elements that install under virtually any flooring, advanced smart controls, and energy-efficient designs. From luxury resorts to everyday homes, radiant warmth provides the ultimate in comfort while reducing energy consumption.

The culmination of over 2,000 years of innovation—from the Baths of Caracalla to your home—proving that the best heating solutions stand the test of time.

Why Electric Radiant Heating Won

-

No Complex Infrastructure No boilers, pumps, or plumbing—just electricity and simple installation

-

Universal Compatibility Works with tile, stone, vinyl, laminate, wood, and carpet

-

Precise Zone Control Room-by-room heating with individual thermostats for maximum efficiency

-

Future-Ready Technology Smart controls integrate with home automation systems and energy management

Ready to Experience the Comfort of Radiant Heat?

Get a free quote for your project or speak with a radiant heating expert today.